Essay

Colin Perry

Marjolijn Dijkman’s work has the potential to induce in viewers a serious case of brow-wrinkled guilt, paranoia, or millennial fantasy. Her subjects, which include ecological meltdown, neoliberal brutalization, and speculative physics, are certainly serious. Thankfully, the Dutch artist’s work is rooted in a gently no-nonsense wit and a general air of analytic calm. Taking the form of site-specific sculpture, video, and photography, Dijkman’s practice explores ideas underpinning the categorical fields of scientific research and museology, and analyses the mainstream propagation of images, cultural norms, and the exploitation of natural resources.

Part of a larger discourse about globalisation itself, Dijkman has exhibited in big-hitter biennials in (for example) Mercosul in 2009, and Sharjah in 2007. A current hiatus in air miles – the artist, I’ve been told, is exhausted – has coincided with two significant solo exhibitions in the UK this year. Presented first at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham in a modest exhibition curated by Jonathan Watkins (who also directed the above mentioned edition of Sharjah), Dijkman’s work is currently on view in an expanded show at Spike Island in Bristol, which has been curated by the gallery’s new Director Helen Legg (who formerly worked as a curator at Ikon).

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, installation at Spike Island, 2011

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, installation at Spike Island, 2011

Dominating both exhibitions is Dijkman’s ever-expanding archive of photographs, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (2005-ongoing), taken at unnamed sites around the world, printed as posters and pasted onto the gallery walls. The artist has deployed a category system to arrange thousands of images around keywords such as: ‘abuse’, ‘civilize’, ‘correct’, ‘demonstrate’, ‘erase’, ‘liberate’, ‘measure’, ‘occupy’, ‘protest’, ‘strike’, and ‘warn’. If the categories sound portentious, the artist has chosen to illustrate them with images that undercut their implied gravity: a kitsch model of dog in a shop display beside a Christmas tree; a faux life-sized horse wrapped snugly in tartan; a model cow standing above a well-positioned milking pail. She clearly enjoys the subversion of systems and words: the category ‘burst’, for example, features images of a smashed bus stop and a ruptured pavement; ‘regenerate’ is accompanied by images of hastily patched up walls and windows (the opposite, of urban regeneration, surely?). More importantly, the photographic project, as a whole, is an exercise in folly – her attempt to map the world from a personal experience could, quite simply, never be enough.

The title Theatrum Orbis Terrarum refers to the first true modern atlas, which was published by Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius in 1570, which translates as “Theatre of the World”. Like Dijkman’s project, Ortelius’ 53-page atlas delimits an understanding of the known world that seeks universality but is deeply compromised by methodological pratfalls – Ortelius’ maps are (quite clearly to modern eyes), rather lacking in crucial details (recently discovered South America looks a bit like modern day France, while undiscovered Australia is a turd-like lump troubling the Antarctic coastline).

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum partakes of a humour that’s not immediately graspable: there’s no clear irony, no cynical parody – just images, one after the next, each demanding to be looked at and each allowed to dissolve into its own mire of iconological absurdity. This cumulative wit is, it seems to me, more prevalent in continental European than in the UK or USA (our humour seems more rooted in verbally punning, text, and bawdiness). Dijkman’s humour is close, perhaps, to the photographic projects of Jean-Marc Bustamante – notably, the French artist’s contribution to Documenta X (1997), Bitter Almonds, was a book containing photographs of anonymous suburban non-sites that Europeanized Robert Smithson’s photographed Monuments of Passaic (1967). Bypassing the cinematic qualities of forsaken suburbia that so intrigued Smithson, Dijkman’s exploration of the absurdity of place and non-place is more akin to a sprawling internet image search, with its miscues and surprises.

Still from Geography is a Flavour (2009-ongoing)

Still from Geography is a Flavour (2009-ongoing)

Dijkman’s critique of the economy of images is evident in another ongoing image-based project: Geography is a Flavour (2009-ongoing) is a video cataloguing snapshots of oddly un-PC visitor centres and theme parks (a collection of tepees, for example, accompanied by a synthetic tribal drumbeat). Geography is a Flavour draws its title from coffee chain Starbucks’ guileless catchphrase, which barely masks the company’s rapacious lust for territorial acquisition. Of course, Starbucks is a synecdoche for neoliberalism – its desire to take hold of the landscape by categorising it as a consumable, unmasked by its own marketing blarney.

Dijkman is engaged with environmental issues that suggest her work might be read as part of an ongoing chronology of ecological art, from Smithson to contemporaries such as Tue Greenfort and Lara Almarcegui. Such artists frequently hone-in on the fuzzy-boundaries between culture and nature, ideologies of progress, and conservation. These concerns are evident in All Alone Amongst the Stars (2007), a project and resulting video work in which Dijkman transported and exchanged two young oak trees from two sites in Europe: the 8,000-year-old Bialowieza National Park forest that spans areas of Belarus and Poland, and a mechanically-planted forest in the Netherlands (Incidentally, Greenfort is also listed as a collaborator on the project).

Still from Surviving New Land (2010)

Still from Surviving New Land (2010)

An equally potent site appears in Dijkman’s video Surviving New Land (2010), which was filmed from a boat and depicts little more than the low horizon of a new manmade area of land recently built as an expansion of Rotterdam’s harbour, constructed by spraying the mind-numbing large figure of 190 million m3 of sand into the sea. A soundtrack adds drama not present in the video: an audio collage from movies about the discovery of new frontiers (Westerns, science fiction, etc). Surviving is an oddly threatening work: the expansion of trade, consumerism – the neoliberal gambit as a whole – are here aligned to the dredging and infilling of virgin hinterlands.

Dijkman rarely makes her art historical precedents clear, but, if we look hard, her engagement with recent art history is evident. At Spike Island, Dijkman presented a sculpture titled The Pleasure of Recognition (2011): a large boulder of the type usually found in zoos or nature reserves and used as a public information notice. The Pleasure…, however, has a mirror inset where the information panel might otherwise be, proffering a rather ungainly view of our own dumb mugs and triggering thoughts of self reflexivity. There is also a subtler joke at play here: The Pleasure… looks not unlike one of Smithson’s sculptures, and draws its title from Sigmund Freud’s description of the enjoyment we humans find in familiar objects or experiences.

This art historical engagement can be found in an earlier work, Storage (2003), made in collaboration with Wouter Osterholt, in which the artists filled a disused shop in Leiden city centre with empty packing boxes and bits of scavenged office furniture. The result bears a striking resemblance to Arman’s famous exhibition ‘Le Plein’ (‘Full Up’), 1960, in which the artist filled Iris Clert Gallery, Paris, with a veritable mountain of scavenged detritus (the work was conceived as a not-so-subtle riposte to Yves Klein’s ‘Le Vide’ / ‘The Void’ installed at the same gallery two years earlier).

The political subtexts of Nouveau Realisme – the ravages of capitalism and urban change – are also evident in the continuity between Dijkman’s re-presentation of torn- up fly-posters in Plakatieren verboten! (2006), installed in a temporary exhibition space in Regensburg, Germany and Jacques Villeglé mid-century decollage posters. Such references are, of course, an aside to Dijkman’s principal concern for the ecology of site and the communal use of space.

Since the early 2000s, Dijkman has been creating site-specific interventions that seek to highlight the mutable aspects of our built environment. In 2004, for example, Dijkman made a dramatic alteration to Gallery Sign, in Groningen, the Netherlands, by building an open passageway from the gallery’s highstreet entrance to the street behind it – thus giving members of the public 24-hour access to an otherwise private space and creating a shortcut for wayfaring citizens.

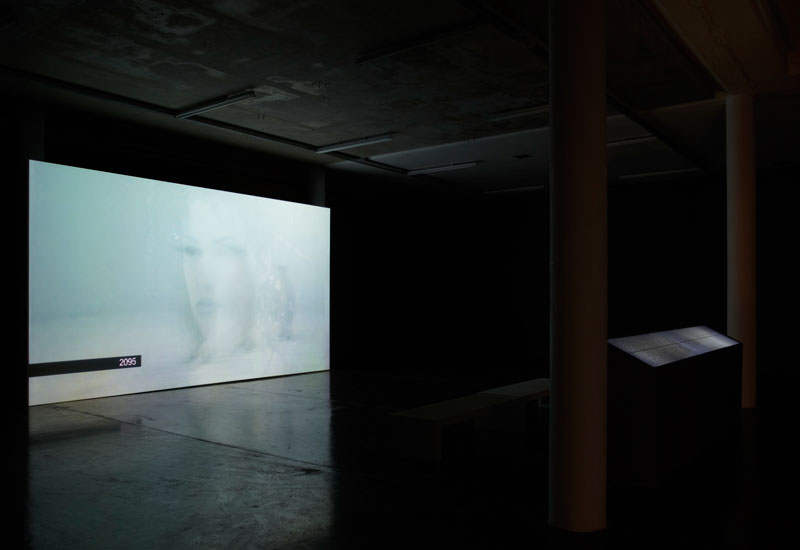

Installation of Wandering through the Future (2007) at Spike Island, 2011

Installation of Wandering through the Future (2007) at Spike Island, 2011

When she was invited to participate in the 2007 Sharjah Biennial, Dijkman was inspired by vast billboard signs advertising new luxury property developments. These signs feature slogans that use promotional language that, the artist notes, “appears to borrow directly from the world of blockbuster science fiction films” – yet, ironically enough, the city’s autocratic government routinely bans the public screening of many of these movies. Dijkman’s Wandering through the Future (2007) is a video made of excerpts from mainstream science fiction movies such as The Day After Tomorrow, 12 Monkeys, and The Matrix, which runs sequentially from 2008 until 802.701 AD. Each excerpt presents a dystopian vision of the future, accompanied by doom-laden prophesies: “The system is perfect, until it comes after you” (Minority Report); “A perfect world of total pleasure, with just one catch…” (Logan’s Run). While the video was made specifically for Sharjah, it also stands alone as a sly dissembling of the neo-religious fatalism, marketable paranoia, and teenage ennui that underpin the plots of such fiction. Wandering… also features an installed timeline, which is printed onto a long, backlit information panel (of the kind you might find in a natural history museum), which maps all the disasters that our collective imagination has inflicted on the future.

As well as her own practice, Dijkman was instrumental in setting up the collaborative organization Enough Room for Space, which aims to “explore critical positions for contemporary art in society”, through supporting disparate artistic ventures in a wide range of locales. The currently active project ‘Present Perfect!’ explores historical and contemporary relations between Europe and Cameroon (involving 10 artists and several critics in the production of an ongoing series of journals, and the establishment of residencies for Cameroon artists in The Hague). Through such diverse means, Dijkman explores the contingencies and margins of global art, connecting localities, and working in and through the current globalised economy in order to draw attention to its oblique and unspoken impulses.