Artist Book

Marjolijn Dijkman

A pocket size publication that gives insight in the archival system and images of the ongoing research ‘Theatrum orbis Terrarum’. There are 8 or 16 images per category that function like an index to the archive.

Marjolijn Dijkman’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is an ever-expanding collection of photographs, assembled since 2005, that observe how people organise their living environments across the world.

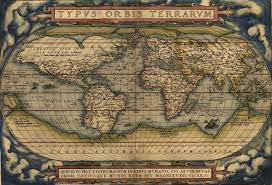

The title of the project references the first modern atlas – a fifty-three page set of maps covering the known world, compiled in book format by Abraham Ortelius in 1570. Ortelius was less a scientist or cartographer than a collector, whose revolutionary achievement was that he brought together a vast body of existing geographical knowledge and unified it into a single, standardised format and logical system. For Ortelius, unlike his successors, cartography allowed the reader to envisage the stage upon which history occurred. The maps were accompanied by texts in which Ortelius provided the reader, ‘tired of travelling’ the globe, with a narrative description of the various regions, animating the abstract pictorial language of cartography with details about people, flora, fauna and produce, along with vivid stories about the fortunes and misfortunes people had endured in disparate places. The wealth of collected histories and myths was accounted for with another novelty: an extensive bibliography, listing all the sources Ortelius had been able to bring together. His Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World) was thus the first truly encyclopedic description of the world. The claim that the atlas was so comprehensive that it could be considered a mirror of the world resonates in a prefatory ode accompanying its 1598 abridged French edition: “This book by itself is the entire world; the entire world is but this book”.

Dijkman’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum questions precisely this totalising claim to knowledge of the Western cartographic tradition and the power over the world this knowledge implied. Her endeavour to assemble a collection of images of places is deliberately arbitrary and subjective. Though the photographs are taken around the world, they don’t claim to cover or represent the entire globe, but are occasioned by what she encounters on her travels, as she wanders around the places she is invited to. Like the counter-geography of the Situationists, the images, all taken at street level, do not suggest an omniscient, God-like perspective on the world, but are located within it. The atlas introduced a particular and highly selective form of representation that helped set the stage for particular kinds of relations to the world – while simultaneously claiming to be mere description. Dijkman’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, by contrast, is not an atlas of landscapes and territories, but an atlas of the ways in which man relates to the world he inhabits.

This growing collection of images is subjected to a cataloguing system that further underlines this shift from mapping a landscape to assembling an inventory of people’s actions upon it. Any information that would tie the images to specific places or people, cultural or economic contexts, is deliberately omitted. Instead, the images are sorted into categories such as ‘adapt, appropriate, conceal, demonstrate, direct, embrace, suffocate’ – all terms which typify the material realities we see as being traces and effects of human gestures.

The project Theatrum Orbis Terrarum manifests itself in different public forms. One is a slide projection, including 9,000 images edited into distinct categories, which are shown one after another over a period of eight hours. One image, however, may be included in several categories and trigger different readings. Another is a panorama of printed photographs, pasted in a grid over several walls, in a fashion loosely modelled on the Myorama – a nineteenth century children’s game, consisting of a set of illustrated cards that could be endlessly arranged and rearranged to form different landscapes. Each time the slide show or panorama is exhibited, it evolves along with the growing and mutating archive, including a different selection and combination of images, as well as new images or even new categories, that may provoke a rereading of the entire collection.

The form of this publication stays close to the original Theatrum Orbis Terrarum reference. But though this book covers all 112 categories of human gestures identified to date and invites the reader to ‘travel’ through the theatre of the human world, it includes only a selection of the images collected so far, organised in a temporary formation, as a moment of repose in an open and mutable process of understanding how we relate to our world.

____