Initited by: Marjolijn Dijkman as part of the WaterLANDS Artistic Engagement Residency

Since 2023: Individual Research

EU Horizon has funded the selection of six artists to each reflect on one of six different ecological restoration sites in Europe as part of the large-scale and ambitious project ‘WaterLANDS‘ (2023-2026).

Marjolijn Dijkman develops ‘Turbid Tides’ concerning one of these six sites, reflecting on ecological restoration and depoldering in the context of the Ems-Dollard estuary and the surrounding landscape in the North of the Netherlands. This will lead to presentations in 2026 and 2027. The estuary is an ecosystem that crosses national borders; this is why she also looks at processes taking place on the German side of the estuary.

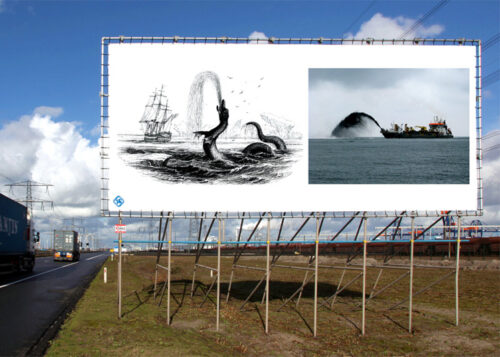

This research, Turbid Tides, presents an intuitive and speculative narrative about the increasing siltation of the Ems-Dollard estuary alongside the growing influence of computational thinking, with silt and data as the main protagonists. She aims to produce an essay film, installation, and publication that will explore shifts in Western thinking about sentience, intelligence, and our place in a more-than-human world.

An artistic approach to landscape projects like this can reveal hidden stories and relationships that might be overlooked. The estuary is depleted of life due to siltation of the water, which is caused by various factors that interact, including dredging, land reclamation, soil subsidence due to gas extraction and peat oxidation, sea level rise, and water management infrastructures like the major dam, the ‘Afsluitdijk’. The water quality problems and the need to reinforce flood defenses have led engineers to consider removing sediment from the estuary in a newly created intertidal area in the hinterland. The silt in the Ems-Dollard estuary can be regarded as a kind of antagonist and, at the same time, protagonist in the story of the recovery process in and around the estuary. When the water silts up, it kills organisms in the water, but at the same time, it can bring a fertile layer of clay to land.

Ecological restoration is part of a philosophical “recovery process” from the dominant European worldview that divided nature and culture to allow for economic exploitation. These projects in the coastal zone require a shift in perspective and a new form of dealing with our environment. In his book ‘The Good Ancestor,’ Roman Krznaric, an Australian philosopher, used the rich history of the construction and maintenance of the dikes in the Netherlands as an example of long-term thinking and intergenerational care. These aspects are essential when considering the restoration process of the coastal zone and its inhabitants.

Documentation of the first walk De Waker (The Watcher), October 2024, photo: Wim Dijkman

Documentation of the first walk De Waker (The Watcher), October 2024, photo: Wim Dijkman

Waker Slaper Dromer (Watcher, Sleeper, Dreamer)

‘Waker, Slaper, Dromer’ is a series of three walks named after the poetic names and functions of dike systems in the Netherlands. Here, the ‘watcher’ first protects against the outside water, and the inland ‘sleeper’ catches any breach. Behind this sleeper sometimes lies another ‘dreamer.’

These events connect artistic research, dike construction, ecology, philosophy, and regional history, offering an in-depth look at the landscape through contributions from various experts, each with their unique and local knowledge. These walks will be organized in 2024 and 2025 as part of Dijkman’s WaterLANDS artist residency.

See for more information: www.wakerslaperdromer.nl (Dutch only)

The WaterLANDS project is led by University College Dublin, Ireland and brings together 32 organisations from research, industry, government and non-profit sectors in 14 European countries.

The artists part of WaterLANDS working on 6 different sites are: Maria Nalbantova (Bulgaria), Elo Liiv (Estonia), Christine Mackey (Ireland), Claudio Beorchia (Italy), Marjolijn Dijkman (Netherlands), and Laura Harrington and Fiona MacDonald(Feral Practice) (United Kingdom).

More information: WaterLANDS Artistic Engagement Residency & WaterLANDS