Conversation

Jes Fernie and Marjolijn Dijkman

This conversation comes from ‘History Rising’, published by Onomatopee in 2015.

Jes: Let’s start with Oliver Cromwell’s wife. She takes pride of place at the beginning of this book. Her head is shown in two positions: one cast down, the other in profile. Why is she here, in a book about museum display?

Marjolijn: She has been on my mind throughout this project. The first time I visited the Oliver Cromwell house in Ely I was struck by the way the museum chose to represent her as this automated mannequin in the corner of a room with very little explanation. For the last twenty-five years, her head has been slowly moving up and down, seven days a week. Many museums use mannequins to draw visitors into a story about a particular period in time, almost like in a movie or a play. These displays have the strange effect of freezing time; presenting history as a static thing that has no porous qualities. In the case of Elizabeth Cromwell, she is presented doing needlework but it is quite mysterious why she is continuously shaking her head, especially since the movement has nothing to do with the act of sewing! Somehow, she is stuck in a loop, forever cast as an ‘extra’ in the shadow of her husband. She made me think about the headlines and the margins of our collective history: What stories take the main stage? Who will be remembered, forgotten or perhaps even worse, completely misrepresented? And how and by whom are these narratives constructed.

The Wife of … HD Video, loop 3:06 min. (2013)

The Wife of … HD Video, loop 3:06 min. (2013)

J: History Rising grew out of an international residency programme we were involved in at Clare Cottage in East Anglia in 2010. What interested you about the place, its history, and the life of John Clare, the 19th-century poet?

M: At the beginning, I was intrigued by John Clare’s outspoken critical and ecological voice, but after a while I became more interested in the representation of Clare at the cottage itself. How, for instance, local members of the Conservative Party had some influence in the development of the museum. I wondered what impact this had on the display of his life story. Critical angles were softened and it was hard to imagine a radical, poverty-stricken poet living in such a whitewashed environment. In a strange way, he won the lottery after his death! In the romantic countryside version of his house, the museum has reconstructed the table where he is supposed to have written, empty beds where nobody ever slept, and a kitchen where no one ever cooked. The altered representation of his life story and private spaces are now open to the public, with the very surreal addition of mental health service booklets in his bedroom (Clare spent forty years in a lunatic asylum, largely due to the effects of the Enclosure acts and his chronic poverty). The way that Clare Cottage tells Clare’s story and edits his life felt like a kind of enclosure in itself. This idea of enclosure not only of place but also of time and our collective or personal stories became fascinating to me and led to a journey through many of East Anglia’s museums, ranging from small to large, publicly funded and private, representing all different periods of time.

J: Take me through a range of these museums – how did their collections and display mechanisms lead you to conceive of history Rising?

M: Well, at first I visited other museums comparable to Clare Cottage, ranging from houses belonging to artists, scientists and members of the aristocracy. I found only one museum of an ‘ordinary’ person: Mrs Smith. Her house and the contents are preserved by committed local residents who wanted to celebrate the fact that she lived independently in Victorian style until 1995, when she was 102 years old. But after some time, I went to any museum that seemed interesting; there’s such a fascinating range of museums out there! One particular museum I felt drawn to was the Romany Museum in Spalding. It’s a private museum that tells the story of Romany life through the experiences of one family. Going there got me thinking about the extreme alienation felt by many Eastern European immigrants who work the land in this part of the UK, a state of affairs that could be considered similar to John Clare’s situation. But of course, this ‘live’ parallel is never touched on at Clare Cottage.

The Secret Nuclear Bunker at Kelvedon Hatch, UK (2012) photo M. Dijkman

The Secret Nuclear Bunker at Kelvedon Hatch, UK (2012) photo M. Dijkman

The Secret Nuclear Bunker at Kelvedon Hatch was another museum that stayed with me for a while. It‘s a large underground bunker at the end of the Central line, maintained during the Cold War as a potential regional government headquarters. In 1992, when it was decommissioned, the government abandoned the whole site. The current owner has no support from the government to research and tell the history or maintain the museum. He made quite strange and outwardly critical scenes with bizarre 1980s showroom dummies, with missing arms and with weird wigs, representing government employees who seemed to have suffered a nuclear fallout of their own. Some are even wearing Margaret Thatcher masks! These kinds of museums, made by individuals, with subjective stories and visions, are so different from the more official English Heritage sites or National Trust properties. This led me to look into issues relating to subjectivity, social critique and the power of display.

J: The huge expansion in the number of public museums in 19th-century Europe and America came out of the founding of modern nation states and the booming historical consciousness that went with it. This collective re-appropriation of heritage meant that museums weren’t merely institutions but symbols of a particular culture and way of life. It’s really interesting to see the development of the museum in parallel with the development of the department store. Both are often free to enter and both offer a form of spectacle to attract the gaze of the 19th-century flâneur. On top of this, the design of museums often mimics the design of department stores, and increasingly take on the guise of high end airports.

M: Yes, I love this collision of culture and commerce. It seems crude to us today, but in the early museums, visitors expected to be told the price of exhibits which allowed them to symbolically possess inaccessible objects. In her essay ‘The Museum as Metaphor’, Chantal Georgel talks about this link by looking at the genesis of the vitrine. Before 1830 these mahogany tables were apparently called montres which were the cases in which glass makers displayed their goods – they enabled people to see but not touch. After 1830 they came to be called ‘vitrines’, a term that was borrowed from interior design, commerce, the bazaar and the department store. Georgel calls both museums and department stores ‘machines of capitalism’. I think that’s a really powerful idea and this has influenced the conception of the works developed for this project.

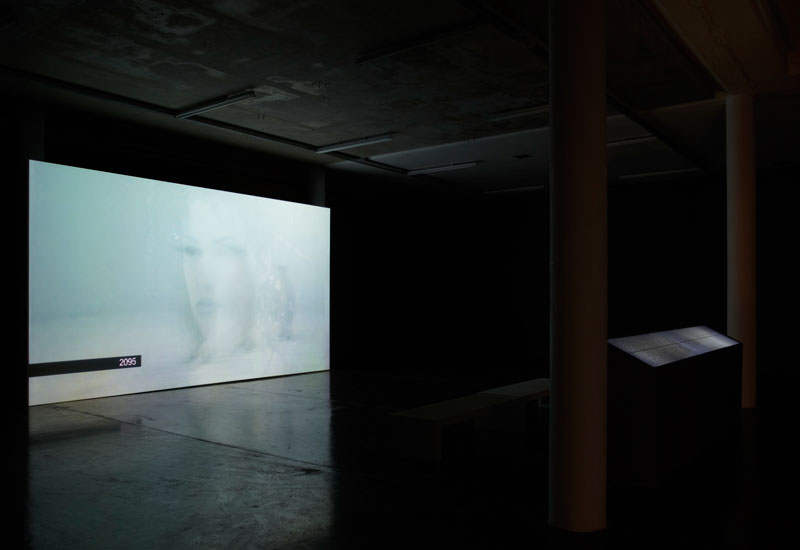

Installation view of Wandering through the Future, Spike Island, UK (2011)

Installation view of Wandering through the Future, Spike Island, UK (2011)

J: your practice builds up a compelling story about the human drive to mark our presence on earth and position ourselves in relation to our past, present, and future. In Wandering Through the Future (2007) for instance you present clips from sci-fi movies that show how much closer the future is getting in our apocalyptic narratives. How are you continuing this theme in History Rising?

M: The accompanying timeline for Wandering Through the Future revealed that future visions from the 1960s and 1970s were regularly set in quite surreal long-distant futures, whereas more recent sci-fi films are often set in the very near future with terrifyingly realistic scenarios. It showed that the space between the notional present and future has shrunk. UNESCO estimates that about 3–4% of the world‘s surface now consists of heritage or protected sites. In a lot of cases, this means the survival of rare traditions and precious natural sites but at the same time, this made me wonder about the impact of this turn to conservation. Heritage became increasingly important when our planet suddenly started to change very rapidly during the Industrial Revolution and increased enormously after World War II. In Britain, for instance, the number of museums significantly increased in the 1980s as part of the Conservative Party’s agenda. Many industrial areas were turned into heritage villages where former factory workers performed the lives of their grandparents. In 1974 there were only around 800 museums in Britain, at the end of Thatcher’s eleven-year premiership, this figure had grown to over 2000.

J: Thatcher very astutely balanced her drive to create opportunities for innovation and capital growth with an appeal to the continuity of tradition in heritage. While the foundations of society were shifting all around us, ‘pastness’ was inserted into the popular imagination. It’s just one of the many great legacies that Thatcher bestowed upon us!

M: This obsession with heritage does seem to be particularly rife in Britain, but in a lecture by AMO about their project Cronocaos, the architects talked about one of their building projects that was not yet finished, but was already marked as a potential heritage site. The space between the launch of a building and it being labelled a ‘heritage’ asset has apparently shrunk as well. The works produced for History Rising relate to the idea of a shrinking representation of the past and future; a sort of vacuum of the present – a form of enclosure.

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Projection), Bloomberg Space, London, UK (2009)

Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Projection), Bloomberg Space, London, UK (2009)

J: Much like your Theatrum Orbis Terrarum project (2005-15) which consisted of an enormous archive of photographs that invite the viewer to travel through the theatre of the human world, history Rising critiques totalising claims to knowledge assumed by particular institutions and cultures. you are saying: look closely here, human history is made up of so much more than these adopted forms of authority. Can you talk a little about this?

M: When I started work on Theatrum Orbis Terrarum it became clear to me that Abraham Ortelius, the man who made the first indexed atlas of the world in 1570 by collecting data of explorers and traders, had no idea what entire continents looked like. The resulting form of abstraction and its impact on warfare, colonisation and trade has been enormous. The perspective used (sometimes called a ‘god perspective’), overlooked many particularities and resulted in a disconnect between what was happening on the ground and so-called ‘facts’. A lot of postcolonial issues dealing with borders in Africa and other places in the world are a direct result of this reality on the ground versus the abstraction of the map. I guess history writing could do something similar but in a more complex way. Mapping time and excavating the past also has to deal with the many gaps in knowledge that are filled up in theory. The further you go back in time, the larger human eras become, and periods turn from thousands to hundreds of thousands to even millions of years. Besides this form of speculation, it is impossible to represent our current period of time without generalising and leaving crucial details out. This relates to Jorge louis Borges’s story of the world map that became so large that it became 1:1 with the real world. Or even better, his story about the man who tried to draw the map of the world only to find that it was a self-portrait. Living in the Past, an experimental archeology project produced by the BBC in 1978, followed a group of fifteen young volunteers recreating an Iron Age settlement. They sustained themselves for a year, equipped only with the tools, crops, and livestock that would have been available in Britain in the second century. Looking back now, it is funny to see how much they represent their own time, talking about issues not very different from other communes at the time. Similarly the museum curator, her or his background, beliefs, and political views always play a part in the representation of the historical narrative and the related selection procedures. To give you a quite poetic example, at Norwich Castle Museum they use different colours for different periods of time in the exhibits: a particular red for the Anglo-Saxon period, yellow for the 19th century, and mint green for World War II. When I asked why these colours were chosen, the curators said that these were intuitive decisions – colours were matched to particular periods of time that ‘felt right’. I have to say that I love the idea of having a colour association with a specific period of history! What colour could the 21st century represent? The details of how objects are arranged, the materials and colours used, the titles that are given, the little differences in museums of similar events – all these things become part of the narrative that’s being represented.

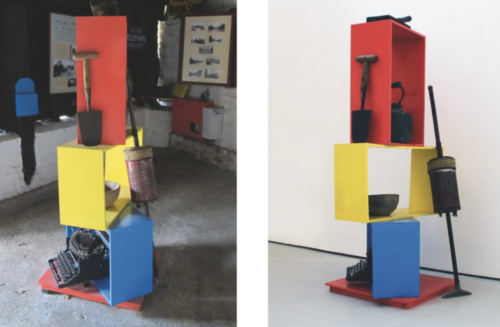

Display at the Denny Farmland Museum, Cambridge / Display of the Denny Farmland Museum at OUTPOST, Norwich (2013)

Display at the Denny Farmland Museum, Cambridge / Display of the Denny Farmland Museum at OUTPOST, Norwich (2013)

J: The curator at Denny Farmland Museum in Cambridge laughed when I asked him if we could borrow one of their farming displays to show in a contemporary art gallery. By placing it in a white cube context you made a powerful statement about the history of modernism and the politics of display. Can you talk about this?

M: After visiting many different kinds of museums I became fascinated by the influence of modernism, even Dutch movements like De Stijl, in museum display structures. At the Denny Farmland Museum, there’s a display structure which reminded me of a Gerrit Rietveld chair. I love the fact that these artists tried to find a new language for a new future that took them beyond history and that this language ended up in a local history farm museum in East Anglia! The more museums I visited the more I started to notice the display structures instead of all the objects displayed. These contemporary museum displays driven by modernist aesthetics do make you wonder: are we here to appreciate the formal qualities of an object or are we interested in the ethnographic context in which it was produced? It’s like a cult of the individual object. Rather than, for instance, packed vitrines showing many different versions of the same object which allows for comparisons and a discussion about different types of use or value (as in ‘old-school’ museums), there is sometimes only one object that’s displayed on a white plinth, spotlit and positioned almost as an artwork. The way some of these displays are purpose-made to present specific historical objects creates a strange merging of modernism and heritage. In the case of the Denny Farmland display, I thought that the display structure and the objects became one installation. When we took it out of the farm museum into the white cube space of OUTPOST in Norwich it temporarily became a kind of objet trouvé. The white cube multiplied the process already happening in the other museum and created a Droste effect, adding another context for the objects to be out of context. Something similar has happened through the process of putting this book together. There is a direct contrast between the 19th-century museum context of Wisbech & Fenland Museum and the white cube environment that I used to photograph the work On the Enclosure of Time. With its simple white walls and concrete floor my storage space resembles a modern art museum. Having everything stripped away in a context similar to a white cube positions the sculptures as artworks or aesthetic objects rather than museological items.

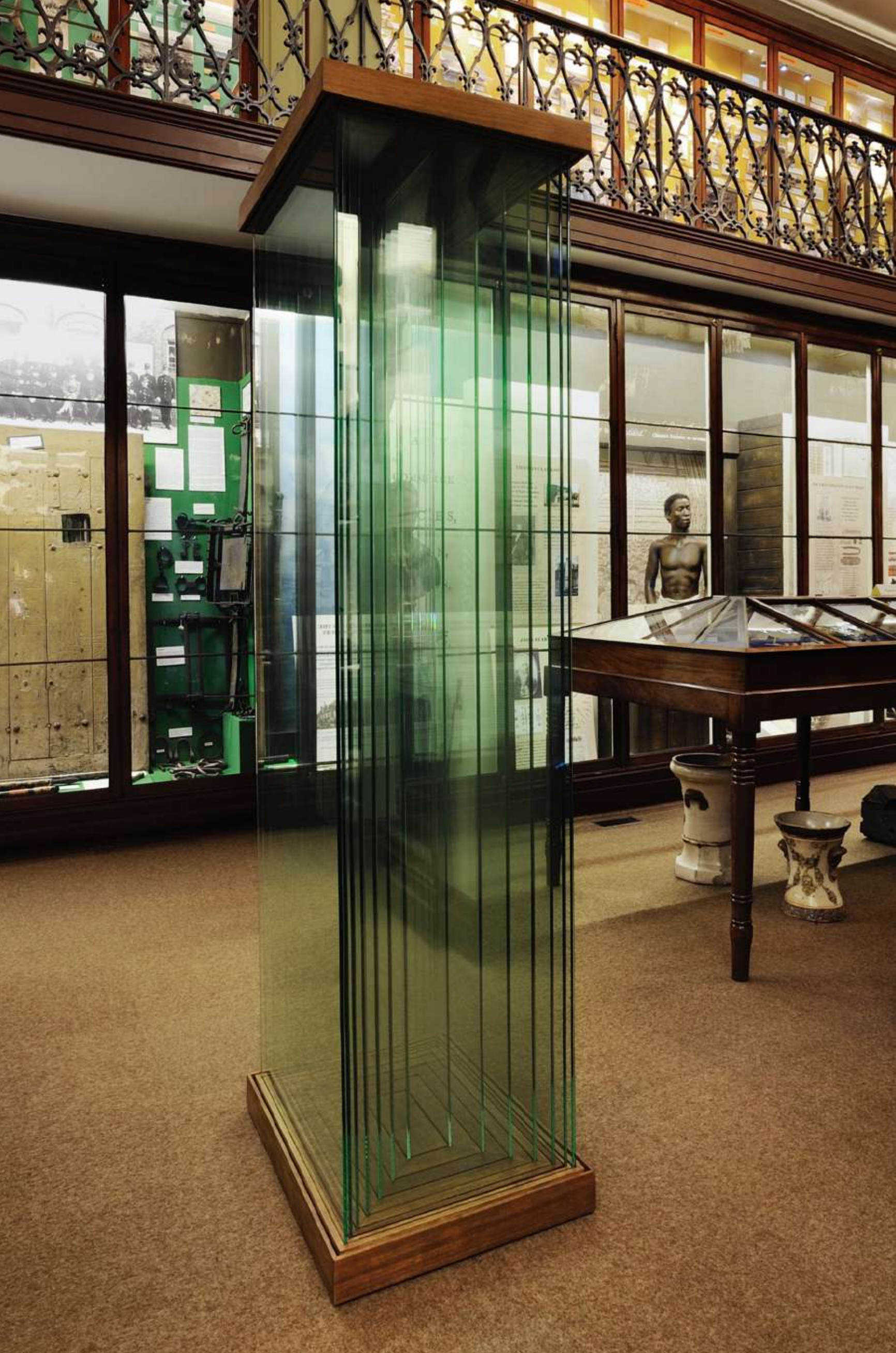

Installation view of On The Enclosure of Time at the Wisbech & Fenland Museum (2014)

Installation view of On The Enclosure of Time at the Wisbech & Fenland Museum (2014)

J: In the works at Wisbech & Fenland Museum and Norwich Castle Museum, you are deleting the object from the equation, focusing on the display structure.

M: Yes, the works reflect on the processes of display mechanisms but also try to take the language of display into a different direction. Display structures normally set the stage for the objects to tell the story but in the collection of works I produced they take centre stage, with their own speculative narratives. The Beginning and The End for example, plays with the idea of the necessary constant expansion and accumulation of many museums, but also monumentalises the current all-pervasive economic growth model. This model is mostly used digitally, not in physical form – by framing it in a display case, the work suggests an ending of its use value. The piece also relates to the transformation of a digital image to a physical sculptural form. The Present is Now Appearing, refers to the process museum curators use to constantly re-contextualise objects through time and simultaneously keep up with the latest museum design trends. The work suggests a kind of artificial growth process in which layers of glass are constantly trying to present, frame, and add a new layer of meaning. The work reflects its environment, twists and distorts it through glass layers, and from some perspectives, one can only see a misty haze. The outer rings in the hardwood top and bottom are left open, leaving room for future expansion.

The Present is Now Appearing, Wisbech Museum, UK (2014)

The Present is Now Appearing, Wisbech Museum, UK (2014)

J: These titles are important, aren’t they? You have re-worked existing museum labelling systems many of which are bombastic, absurd and often sound like metaphysical tracts.

M: It has really struck me how museums adopt this all-knowing, encyclopaedic ambition with displays that proclaim a beginning and an end to a particular narrative. It comes across as pretty ridiculous and sometimes quite funny. In doing this, museums assume control of our future, as well as our past and present. I like the idea of making a display that is open-ended and can lead its own life. The Problem of Currency is a reference to the abstraction and dematerialisation of money and in Finding an Identity I’m making a comment on migration and the recent move in Western politics towards a right-wing agenda. The title of the project, history Rising, comes from a billboard in Dubai that was promoting the Burj khalifa – currently the largest building in the world.

New Horizons (part of On The Enclosure of Time), 2014

New Horizons (part of On The Enclosure of Time), 2014

J: As we walked round one of the many farming museums in Norfolk, East Anglia, you became interested in the wheels that were discarded around the site, as well as those that were on display. New Horizons came out of this interest.

M: The little red wooden wedges positioned on the floor are a play on a commonly used museum display system that stops wheels turning in agricultural or transport exhibits, known as ‘chocks’. There is a suggestion here that we consider the controlling mechanisms of museums; wheels become trapped in time, unable to create a vital relationship with the present, forever repeating the past. But at the same time, maybe these little chocks are pointing towards new directions, in search of alternative horizons.

J: This interest in the relationship of museum display to speculative or potential futures is more pronounced in the development of new works for History Rising. For example, in the work Victory Models referring to war displays you encountered, III has been added to II and I. Are we being asked to devise our own possible future narratives?

M: In a way, museum displays represent a certain truth about where things have come from, but what if a museum display starts to speculate, predict, or anticipate what is to come? What if it started to see continuations in the narratives constructed? I guess this relates to the current non-sustainable present and my general concern over whether we will be able to find a viable future. The works do not really point to optimistic futures and many are critical of the combination of the Enlightenment, modernist, and capitalist ideology that is part of the origin of the museum that we discussed earlier.

The Wisbech and Fenland Museum, UK

The Wisbech and Fenland Museum, UK

J: The Thomas Clarkson display at Wisbech & Fenland Museum sets the museum apart as an institution that isn’t scared of raising potentially disturbing truths about Britain’s colonial past. Clarkson was an abolitionist who lived in Wisbech as a child; the display includes a mannequin whose hands are shackled. How did you incorporate this metal chain into your piece Please Touch / Please Don’t Touch?

M: The Clarkson display was one of the many reasons the Wisbech & Fenland Museum stood out as a potential site for our project. I soon noticed that the most popular period of time represented in museums in East Anglia is the Victorian era. Considering that this period ran parallel to the peak of the British Empire, it was disturbing to see how disconnected museum displays were from global history and a broader political context. One scene at the Museum of East Anglian Life in Stowmarket represents a Victorian classroom, with an English flag and an old colonial map of the Empire shown in relation to other former European colonies without any explanatory text. It just seemed incredible to me – this type of historical vacuum.

J: This kind of ‘whitewashing’ of history to produce a more palatable version is mirrored in much contemporary political manoeuvring. In their desire to tell a good story and capture the imagination of the populace, many right-wing politicians are raiding the history books in search of flamboyant characters, revelling in an idyll of a past never realised. This harnessing of nostalgia for political gain can be seen in the American Tea Party’s adoption of costumes from the 18th-century Boston Tea Party as well as Geert Wilders’ (leader of the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands) adoption of the character of Michiel de Ruyter, the 17th-century Dutch admiral.

The making of Please Touch / Please Don’t Touch, Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse in Dereham, UK (2013)

The making of Please Touch / Please Don’t Touch, Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse in Dereham, UK (2013)

M: This reminds me of Adam Curtis’ documentary series ‘The Living Dead: Three Films about the Power of the Past’ in which he shows well how the Nazis created a version of history that told people: ‘You come from a very important past and you are destined for a very important future.’ But to come back to the work, the title Please Touch / Please Don’t Touch refers to the many signs in museums that control your relationship to the objects on display. Museum barriers demarcate time as well as physical space; here the present ends and the past begins. In Please Touch / Please Don’t Touch, a loosened demarcation itself is the object on display. The design of the chain is indeed based on a segment of a chain on display at the Wisbech & Fenland Museum which is, in turn, inspired by a chain on display in the National Museum in Dublin in Ireland. The original shape of the chain probably stems from a Viking design and has been extensively used throughout time due to its simple production and inherent strength. We made this chain in a public workshop in the foundry at Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse in Dereham, normally used for craft demonstrations. The museum itself has a complex history involving a long period as a workhouse. For a long time, this history was too raw to deal with and wasn’t part of the museum display until the 1980s. Currently, the display is pretty lurid and child-friendly but this approach doesn’t seem to work either. These kinds of processes are part of an ongoing problem that is inherent in the nature of museum display.

The Grand Release, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich, UK (2013)

The Grand Release, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich, UK (2013)

J: All this critiquing aside, the works are sculptures – dumb and strange in their blindness. How do you relate to them as physical objects that take up space in the world?

M: It was quite unexpected that I would end up with a large collection of objects as a result of this project since my works often are more ephemeral. I like how some of the works interact with the audience. The Present is Now Appearing for instance encouraged people to move around the sculpture to get lost in the reflections. Another work, The Grand Release, installed in the central atrium of Norwich Castle Museum, interacts with public activity around it. When the museum is really busy the mobile swirls around and when there are few people in that space, it finds an equilibrium. Apparently, the average lifetime of a ‘permanent’ exhibit is about thirty-five to forty years. Quite similar to what is estimated for many public artworks. I had this in mind when choosing materials and thinking about the work’s presence in time. I made all of these sculptures in my studio in Brussels with the help of assistants – a huge undertaking, given the amount of time involved. It was important to me that we hand-crafted all of the elements. The handmade quality of many display structures, especially in some of the smaller museums, I find appealing. The crafted wood, soft felt, and fabric materials used for the displays reveal traces of the individuals involved in the making. Today, many of the displays are made from plastic or glass; they are dust free, climatised and almost unaffected by the elements or time. I preferred to use materials that will decay, lose colour, and reveal visible traces of the individuals who made them.

J: And finally, the works are playful and slightly scurrilous aren’t they?

M: Humour plays an important part in a lot of my work. There is always a certain light-heartedness about the works themselves, even if the issues they raise are serious and the research carried out is quite elaborate. Often, my works are invitations to engage with specific issues, without giving straight answers or concrete alternative proposals.

____